|

|||

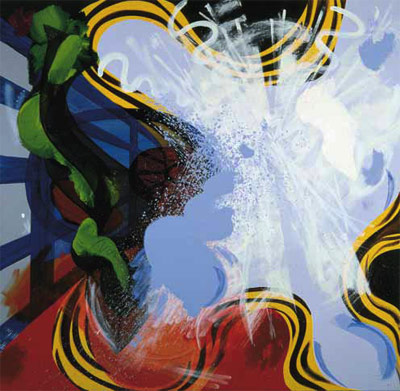

Advancing Warm Front, 1993

A Surface on which

to Dwell, 1984

Leaping Laocoön, 1985

Bifocal Bender, 1989 | |||

|

|

|||

Carter Ratcliff: Let’s start where you do, in the studio, at the moment when you make the first mark on a blank canvas. Richard Hennessy: Well, that’s a moment fraught with a sense of the momentous. A plunge into the unknown. Because, no matter how long you have painted, no matter how much experience you have accumulated, you can never completely predict what the mark you make with your brush will look like. You make the mark and then you have to react to it. And your reaction may not be immediate. It may take a while—for me, at any rate, because I never start with a plan for how to proceed. Plans make it all too easy. They relieve you of the need to pay attention to what you’re doing. Just following the plan through to the end isn’t challenging. A painting acquires interest by becoming a record of the interaction of mind, matter, and physical activity. Choosing. Preferring. Judging. Making. CR: And, eventually, the painting is done. But what about preparatory sketches? Notes toward an overall composition? I’m reminded of how-topaint books, with their advice on blocking out the main elements of the composition and so on. RH: Well, the ‘main elements’ emerge from the process, as does the subject— the poetic content. They can’t be rushed into existence before you’ve picked up your tools and mixed your colors. I compose as I paint, from within color. From within stroke. The oil medium makes this possible, though there is, of course, an enormous prejudice in favor of drawing coming first and painting later. That’s about fresco. Because of the nature of that medium, a fresco painter had to work everything out in advance. But not all great painters did that. That is why there are so few Titian drawings, and almost none whose attribution isn’t controversial. There are, perhaps, two drawings by Velazquez. That may be merely an accident of survival. But both these painters worked directly on the canvas. In the wet. Monet, whom I rank with Titian as one of the greatest technicians of all time, is very much to the point. People have recently tried to make a case for the unknown Monet— Monet the draftsman. Yet his drawings are not artistically interesting. His compositions were not planned in advance, on paper. They emerged from the process of painting. The color-space which resulted is one of the most august and original achievements in all of painting. CR: What about Michelangelo’s drawings, and the Florentine idea of art those drawings do so much to sustain—disegno and all that? Surely those drawings are great in their way, even though Michelangelo may not have prized them as much as we do. He thought of himself as a sculptor, and I think it’s arguable that his drawings are not all that pictorial. Or if that is a silly thing to say, isn’t it nonetheless true that his drawings are not about pictorial space? They look to me like notations of form, and often the forms just float on the page. They’re the drawings of a sculptor who painted under protest. Maybe he would have liked to refuse the Sistine Chapel commission, but how could he? Ultimately, though, he was right about himself. He was a sculptor. And an architect. RH: A very great architect. As for the drawings, they’re about mass and compressed energy. They’re the greatest drawings about mass that have ever been done. You really believe in the solidity of those figures—and every grain of notation counts toward that effect. I recently gave a talk at the New York Studio School, which led me, at one point, to put a Mondrian and Rothko up on the screen. Then I followed up with Michelangelo’s God, creating the sun and the moon. Both arms are extended, the fingers pointing intensely. And his gaze is intense. With his left hand, he is creating the moon. With his right, he is creating the sun and pointing right at it. Talk about eye-hand coordination—a completely unified body-mind. One substance, with the power to create a universe. For centuries, Christian Europe had been oppressed by the image of a man with both his hands nailed down. Fortunately, determined efforts to nail down the mind as well proved unavailing. With the advent of the Renaissance, the body returns in all its glory. With Michelangelo, we get the world’s most famous image of touching— the creation of Adam on the Sistine ceiling. CR: I wonder about Michelangelo’s religiosity. Of course, he was religious— a Catholic in the manner of his time and place. But his idea of art was Neoplatonic. Pagan. His David is Hercules. So I suppose there is no way of knowing just how much piety we should see in his images of the Scriptural god. RH: Michelangelo’s God is the same as humanity’s—an imagined ideal agent, an ideal doer. No doubt an idealized self-image. Or so it seems to me, as a painter. But I am getting into risky territory here. It has to do with pride and what we all love about painting—the spectacle of a world emerging from the painter’s hand and mind, from one’s body and one’s mind simultaneously. To paint is to unify one’s being. So there may be an element of self-portraiture in Michelangelo’s images of a god that is all of a piece. Of course, the ancient Greeks talked of a sound mind in a sound body, and yet there is also the Christian view that man is created in god’s image. And the body was never thrown away. It was going to be resurrected. That’s the thrill of painting, to assert this exalted idea of the body, though there are moralizers who would think that’s over reaching. Isn’t that the perfect word: overreaching? Because reaching is what you do with your arms. That acceptance of—or insistence on—the earthly body is owed to humanism, which gives us a set of very exalted ideas about what we are. CR: Ideas that are of no use whatsoever unless you’re concerned with who we are. Many of today’s art-lovers turn to art as if it were a hot-air balloon, a way of lofting oneself far above oneself. Far above life as everyone else knows it. The other day you were talking about a show of early Cubist work you saw in a gallery on 57th Street—paintings and collages, with their bits and pieces of readymade imagery. No doubt these were shocking when they first appeared: scraps of ordinary life in the exalted realm of art. I suppose the idea, in part, was to flaunt the ordinary at the expense of the exalted. Which is all well and good, and yet one of the effects of collage was to suggest a new and improved way of putting a painting together. RH: Juxtaposition versus composition. CR: Exactly, and it looks to me as if this turned into one of the 20th century’s standard routines. How to make a picture. But not in ten easy lessons, because no lessons are required. RH: True. It’s easy just to make arrangements, to place one image next to another until you’ve filled up the surface. Collage can be an evasion of composition, which is the core issue. And, as familiar as collage has become, for some it still has the look of a challenge to tradition. A faded look, to put it mildly. Nonetheless, I don’t want to deny the greatness of the very first collages or of Analytic Cubism in general, its dematerialization of mass; separating the contour, the edge, from the mass, then atomizing it. Mass becomes this glowing, spectral, atomic vision of itself. Extraordinary. Then Mondrian came along and tidied it up. CR: And once he had done that—once he had shown the way beyond the clutter of Cubism, all the messy ambiguities—he launched the grand project of repeating himself for the next two decades. Not quite fair, of course, but there does seem to be something fanatic about carrying on as if one’s style were the style. The only one that humanity would ever need. RH: What we have to remember is that not so very long after he and Braque invented collage, Picasso was painting neoclassical works, those ponderous figures that look as if they’re made of stone. Having dematerialized mass, he now proceeds to paint bodies as heavy as anything that has appeared in the history of art. For Picasso, there are no permanent resting spots. You arrive at a certain place and then you go on. I believe that all things human are provisional. Nothing is permanent. But the people who saw in Cubism the key to pictorial structure had a conversion experience. Flat, squaredaway form became the be-all and end-all, and I think that began the process of the emptying out of painting, with wilder and wilder claims of moral righteousness. I admire Mondrian enormously, up to a certain point, but I think his painting shows us the prettiest face that fanaticism managed to put on in the 20th century. With his mature style, he equates rectitude with rectangularity. The less going on, the greater the claims. But when does rigor become rigor mortis? When does MoMA become an acronym for Mummies of Modern Art? CR: Are you thinking of the utopian schemes that were funded, so to speak, by the metaphysical certainties of Mondrian and other painters of de Stijl? Not to mention the artists of the Bauhaus and Constructivism? RH: Yes. These were artists who had all the answers. They were going to teach everyone how to live. Answers have only a temporary usefulness. The search is the interesting thing. Whenever an artist pursues an ultimate solution, I become suspicious. The origins of Mondrian’s fanaticism can be seen in a painting from 1912, called Evolution. It’s figurative, thus an embarrassment for people who promote Mondrian’s later work. There are three panels, with a nude woman in each. The one on the right bears a Star of David on each of her shoulders. The one on the left, while not allegorized, I assume to represent Christianity. The one in the center seems to stand for the new religion Mondrian was always looking for, and only her eyes are open—staring bug-eyed. All three of them hold their arms pressed to their sides. But it’s more than that, almost as if their arms were growing into their bodies. Exactly the opposite of evolution. What does this tell you? After all, arms are what we need to paint. The denial of the body built into this kind of abstraction. CR: Paintings have to be painted, as a practical matter, but you’re arguing that painting of this kind implies a bodily image. The flesh devolving to some early stage of embryonic development, while the spirit—or the mind—leaps to a higher level. A higher level and a very narrow one, where the mind can conceive of painting only as a blueprint for utopia. RH: But this denial of the body can be seen in the work of abstract painters who were anything but utopian. There is an early Rothko, from 1941 or ’42, called Crucifix, that shows arms and legs in piled-up boxes, looking like a Louise Nevelson. On top is a head. Or three heads: profiles, left and right, and in the center full-face. One thinks of Christ and the two thieves, crucified. I was stunned the first time I saw that painting, like a body blow. I suddenly realized that the boxes we see stacked in the abstract Rothkos are like those limb-packed boxes. His later paintings are headless, armless, legless trunks. So that appears to be the price of admission to this kind of abstraction. Your arms. Your legs. Your head. CR: Whatís left of the body is a ruin, like an antique statue with its extremities missing. Of course, there is a romance of the ruinóthink of Northern Europeans wandering around the Mediterranean in the 18th century. The Grand Tour, upon which one did not set out without a supply of stock responses to things that had fallen into disrepair. Or been subjected to vandalism. The Acropolis owes much of its decrepitude to the explosion of a 17th-century ammunition dump. Thatís how the Turks were using it in those days. No one blames them, really. Itís almost as if they are to be credited with aesthetic refinement, as unconscious as it may have been. With so much of the past in ruins and the modern spirit so given to doubts about itself, ruins become a sign of integrity. Of authenticity, to use a modern word that goes some way toward justifying the modern spiritís self-doubts. Think of those sculptures of Rodinís that present just a fragment of the body. The irony of the part with the presence of the whole. But not all ironies work. Maybe those fragmented bodies of Rodinís ought to be seen not as grandly monumental but as sadly mutilated. What’s left of the body is a ruin, like an antique statue with its extremities missing. Of course, there is a romance of the ruin—think of Northern Europeans wandering around the Mediterranean in the 18th century. The Grand Tour, upon which one did not set out without a supply of stock responses to things that had fallen into disrepair. Or been subjected to vandalism. The Acropolis owes much of its decrepitude to the explosion of a 17th-century ammunition dump. That’s how the Turks were using it in those days. No one blames them, really. It’s almost as if they are to be credited with aesthetic refinement, as unconscious as it may have been. With so much of the past in ruins and the modern spirit so given to doubts about itself, ruins become a sign of integrity. Of authenticity, to use a modern word that goes some way toward justifying the modern spirit’s self-doubts. Think of those sculptures of Rodin’s that present just a fragment of the body. The irony of the part with the presence of the whole. But not all ironies work. Maybe those fragmented bodies of Rodin’s ought to be seen not as grandly monumental but as sadly mutilated. — RICHARD HENNESSEY has sailed the high seas of painting––widely and freely ––for more than forty years. Always aiming at a comprehensive style, with composition as his overall concern, he has steered well clear of the extravagant asceticism of the anhedoniacs and the stolid klunkiness of pile-it-on bricoleurs. When he felt obligated to speak out, he wrote essays, five in all. CARTER RATCLIFF’s books of poetry include Fever Coast and Give Me Tomorrow. Arrivederci, Modernismo will be published by Libellum Press later this year. A contributing editor of Art in America, he writes frequently about American and European art. For the complete article purchase The Sienese Shredder #2 Back to The Sienese Shredder #2 | |||

|

Sienese Shredder Editions