|

|||

Four Panel Green

Big Green, 1956-57

Film stills from Birth of a Nation, 1965

Lakefront Property, 1959-61

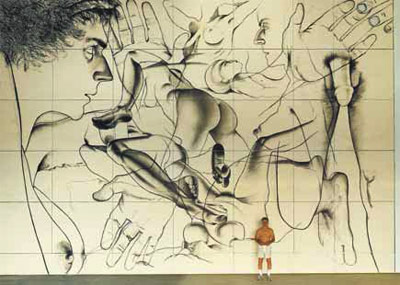

Alfred Leslie in

front of Quotidian

Landscape,

1986 | |||

|

|

|||

Probably no American artist has had a decade as wildly prolific and tumultuous

as Alfred Leslie’s in the years 1956 to 1966. At the outset of this

brief

amazing run, in the latter fifties, Leslie carried Abstract Expressionism

to

new heights of graphic vehemence. At the same time, at the behest of what

he later called his “octopussarian impulses,” Leslie began

exploring other

creative possibilities: writing, photography and, above all, experimental

film. The “Beatnik classic” Pull My Daisy was screened in 1959,

followed

by The Last Clean Shirt (1964) and Alfred Leslie’s Birth of a Nation

(1966).

Then, to the consternation of his Ab-Ex partisans, Leslie’s paintings

began

to change. In the early sixties, visitors to his studio were confronted

by

giant grisaille portraits, often female nudes, standing in stiff, utterly

un-

Beatnik solemnity. Each of his three main bodies of work—the abstract

paintings, the films, the monumental figures—was singular and extreme.

And yet, in an art world notoriously hungry for signature style, Leslie’s

triple resumé made him less, not more visible. Audiences couldn’t

decide

which Leslie was Leslie. And the best opportunity to correct the situation

went up literally in smoke. Late in 1966, as he was preparing for a midcareer

retrospective at the Whitney, a disastrous fire destroyed the contents

of Leslie’s studio. A handful of lost paintings are visible in footage

shot by

visiting film crews. The canvases themselves—approximately fifty

of

them—not to mention drawings, notes, and hours of film, were destroyed. Alexi Worth: Your movie, The Cedar Bar, is a kind of talking portrait of the Abstract Expressionist circle, set in August 1956, in the week after Pollock’s death. At that time, you were already an established abstract painter, though not yet thirty years old. How did you see yourself in relation to that group? Did it matter that you were a generation younger than most of them? Alfred Leslie: The only one who seemed troubled by the age difference was Rothko. By and large there was a great breadth, a great sense of acceptance at the Cedar. I remember walking in one time with David Smith, and a few minutes later Bradley Walker Tomlin came in, and Edwin Dickinson, and we all sat at the table together. And David said, “Look at the spread of generations.” That was beautiful. AW: It was a pretty competitive, conflict-prone situation, wasn’t it? AL: I never felt any competition with them. They were my friends, the people I saw every night. What passed for conflict was mostly just different styles of delivery with a bunch of very serious drinkers. Of course, there were some ideologues at the Cedar. But to me, that always felt antithetical. My own view of Modernism was that it was an opening up, a looking at other cultures, an inclusiveness, not a narrowing down. And think about it: Kaldis, Resnick, Rothko, Reinhardt, Cage, Steinberg, there’s lots of different points of view there. AW: At that point, you were making very spare gestural abstractions, paintings like Six Panel White, and Big Green. AL: They were the most minimalist of my pictures. Six Panel White is what it is: six panels, all off-white. That’s the whole painting, with three or four lines drawn across it. Everything brought down to brushstrokes. Those pictures lacked the physical graces the later paintings had, but I loved them. AW: Why did the paintings gradually become more “graceful?” AL:Well, at first the paintings were all made with housepaint. Leonard Bocour (the paint manufacturer) said, “Give me a collage and I’ll give you some oil paint.” I was penniless at the time, so the economics of it were unbeatable. I would give him a collage, just a little one, six by six inches, and then go to his factory and get thirty gallons of paint. Like that! I put them in a hand truck, and I trundled them back to my studio. Now that paint, it was real oil paint. It had an ambivalence, and a painterliness to it. The pictures started becoming more and more voluptuous. My paint surfaces used to be like a Bronx kitchen cabinet. Now everything came out too fucking beautiful. Too much pyrotechnics. It was getting worse and worse every day. AW: Michael Fried wrote a fascinating review of some of these paintings. He thought you were deliberately overplaying the painterliness—that you were in effect saying, “I know the drips are sentimental, but I have the courage to be really sentimental, see?” Was that how you felt? AL: Yes. And don’t forget, this was the time when (Ab-Ex) painting had become totally acceptable. The sense of challenge was diminishing. For me, it was the beginning of the transition. I said to myself, you can be a painter but a lousy artist. Or you can be an artist, but not be a painter. So I said, What am I? AW: Were you already thinking about writing, about making films? AL: I made my first collage films in 1949. One of them, Directions: A Walk After The War Games was screened at MoMA that year. But I decided that, if I ever was going to mature as an artist, I had to focus on a single discipline. So I paused with that other stuff for a bit. I sold my camera, sold my typewriter. I thought I needed to have a single public face. When I did start writing and taking photographs again, I kept it private. It became a kind of secret life. AW: It seems very fifties: you were a closet multidisciplinarian. What kinds of things were you working on? AL: I wrote what eventually became The Cedar Bar and The Chekhov Cha- Cha. I began the mugshots: Polaroid portraits of pretty much everyone who came into my studio—there were hundreds of them. I was painting, making silkscreens. Everything was overlapping. And one day I just said to myself, Go for it. Let the multiple disciplines decide who you are. — ALFRED LESLIE shows his paintings at Ameringer Yohe Gallery in New York City. Among his many honors he is the recipient of a Gold Medal for Art for his life’s work as a painter from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a Lifetime Achievement Award for his films from the Chicago Underground Film Festival. His latest film-work is The Day Lady Died and 3 Other Poems by Frank O’Hara (2007). ALEXI WORTH is a New York painter who has written about art for Artforum, The New Yorker, and other magazines. He is represented by DC Moore Gallery. For the complete article purchase The Sienese Shredder #2 Back to The Sienese Shredder #2 | |||

|

Sienese Shredder Editions